I realized I probably should fill anyone who reads this in on exactly who it is I’m looking for.

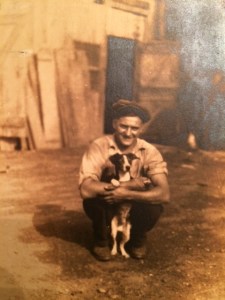

When I was talking about the picture I saw in my head, this was it. I found this picture in the same way I found all the pieces of my Grandpa’s life. They were collected, magpie-like, from Grammy’s house. This picture, taken when he was probably in his late teens or early 20s, was found in a crumbling photo album with those black pages and sticky corners. I have a ring of his. Gold, with an amethyst. I found it in a coffee can under her sink.

He was the produce manager of Donahoe’s Market in downtown Pittsburgh. He’d lived with the Brenckles since they’d adopted him and had worked in their fruit stand in the Strip District for a long time — even after he left their house. He met my Grammy at Donahoe’s and they’d gotten married not long after. He didn’t serve in WWII because he’d been sick as a child and whatever he had, probably strep throat, damaged his heart valves.

He and Grammy had my dad first and then my Aunt Mary Ann. They lived in Hazelwood, then moved to Kennedy Township and the house he built on Ehle Avenue. He lived less than a quarter mile away from his brother, Joe. Their sister lived at the Fresh Air Home in Sewickley until it closed, outlived both her brothers and died just before I was born.

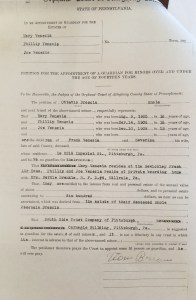

All this digging made me remember that a long time ago, I’d unearthed Grandpa’s baptismal certificate. It was in a strongbox at the bottom of Grammy’s bedroom closet. It had a few closed bank account passbooks, a few other random papers and, I saw, to my awe, the names of my great grandparents.

I went back out to Ehle Avenue this week, where my Aunt Mary Ann lives now, to make a copy.

She was only 13 when her dad died. My dad was 17.

We were in the kitchen, sitting at the kitchen table I’d sat at a thousand times. The smells were all the same. Toast. Puffed Wheat. Folger’s Coffee in a giant can in the pantry. Clorox under the sink.

I asked her the questions I always asked. What did she remember? What was he like?

“You know what Grammy said. He was a piece of bread,” she said. “I don’t ever remember him yelling. He was like your dad, always joking.”

She’d done some remodeling since moving in to Grammy’s old house and I wondered if she still had the concertina.

“Tell me about it again.”

“Well, one night, Grammy heard music coming from down the basement. She thought it was the radio. But when she went downstairs, my dad was sitting there playing the concertina. He was playing ‘Sweethearts on Parade.'”

Then, she surprised me.

“And I remember your dad had this Davy Crockett hat. You know, the one with the tail on it? Well, my dad took it. Then he went down the basement and called her. And when she opened the door (she pointed to the cellar door, next to the stove). He was laying there on the top step. It was on his head but all you could see was the hat. You couldn’t see him. He flicked that tail and Grammy screamed. We all screamed. Until he jumped up and then we were all laughing so hard. We couldn’t breathe.”

I laughed, too. It was so like my dad. My childhood was full of silly pranks and gotchas. I’d never thought about it coming from somewhere other than him. Behind that thought, though, was another. A lot of people come through really hard circumstances. And, well, not everyone comes out with a good sense of humor.

Recent Comments