He would have been 110 today.

There are a lot of assumptions in that sentence. That he would have made it this long. That he’d be one of those knobby-kneed Italian men, drinking wine and toasting his still-dark hair.

As it was, he got a bit more than half of that.

I watch my father with my little girl and I ache all over again for the hole in my life — and in his life, my aunt’s and Grammy’s — the combined negligence and abuse of Ottavio, Pasquale and Mike Natale created. For the bad luck of needing heart surgery just as effective modern techniques were being developed.

He had crazy strokes of good luck for so long. Luck he used to push his brother farther. His sister to more safety. His wife to a safe harbor of a loving man. To stay as long as he could for the children whose 1950s-era Baby Boom world he couldn’t understand, but loved just the same. Sometimes, I feel that luck has been passed down the way his chin has. I just wish a little had been left over for him.

But maybe, just maybe, he felt lucky to be where he was, just as he was.

I am so close to the end. I’d hoped to be done by now. I’d set a goal long ago to mark Grandpa’s 110th birth anniversary with a completed novel and open the search for an agent. But. Life gets in the way. Raising a child and working full time at a great and busy job gets in the way.

I get to thinking that I dip my toe into his world, and he lived it every day. I can take a break from it. He never did.

So. I course-correct. Re-commit to getting done, even if it means less sleep for a while. People have lived with worse.

The Bellaire chapters are hard. They are dark and angry and fraught with tension. Sometimes, I sit in front of my computer, hand to mouth, not wanting to write the next natural thought that proceeds from all the research I’ve done. There is hope, but I see, through the glass darkly, how far away it seemed.

So I turn to music to power through.

Lately, the two albums on heavy rotation have been the work of Broadway wunderkind Lin-Manuel Miranda. Hamilton, and the Moana soundtrack.

I choke back tears every time I hear the chorus of the closing song “Who lives, Who dies, Who Tells Your Story?”

Because that’s what this is, isn’t it? 110 years past his birth, 53 years past his death, I am telling his story. I am making judgments about who is worthy of honor, and who fails at humanity. Are they right? Are they the same ones he would have made? I hope so. I keep remembering that these people are not characters. They were human beings, with complex lives that leave them neither damned sinners nor glorious saints. Except maybe you, Mike Natale. Except maybe you.

And then there’s Moana. The story of a girl who longs to know who she is. Who feels pulled by forces she doesn’t understand until she realizes that what she is isn’t weird. She’s exactly who she’s supposed to be. And the quest she goes on to find herself, it’s epic.

In a lot of ways, these ten years, they’ve been my quest. To fill in the missing pieces of three generations of souls. I know it’s folly to think I alone can bind wounds that were never mine to manage. Still, the words of the movie resonate. “And the call wasn’t out there at all; it’s inside me.”

I almost don’t want all this writing and researching to end. In the movie, just when Moana is about to give up, her Grandma Tala appears. And I’m in tears again because not only does it remind me of Grammy, it makes me miss her so. I know that Phil is right there next to her. For 10 years, they’ve been right there. I got married. I had a baby. I changed jobs. There were times when I thought that what I was doing was stupid and a waste of time. That this will never see the light of day and even it if does, it won’t be good enough.

But.

I’ve spent 10 years in his company. 10 years knowing so much more about him than I did the day I put my head down on my desk in my miserable office in Pittsburgh and pulled it back up with his name ringing in my brain.

Over and over, his memory has raised my head and challenged me to live the life he started but never got to finish.

To quote another Hamilton lyric, “that would be enough.”

Because his name, Joe’s name, Mary’s name. They mean one thing. Love. I can’t speak for all families. I only know mine. But there’s a truth there. Love will come from somewhere. Family will come from somewhere. It can tear you apart, but it can also literally save your life. Phil’s blood betrayed him. A stranger held out hope and a hand. It changed the course of 10 lives and counting.

Over and over again, it’s come back to me.

Lin’s amazing, immortal pronouncement. A truth I see in 110 years of history.: Love is love is love is love.

I just got back from the Brenckle Family Reunion. And oh boy, did I once again hit the motherlode.

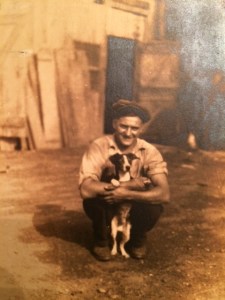

I just got back from the Brenckle Family Reunion. And oh boy, did I once again hit the motherlode. This next one is just Phil with another one of the farmhands. It might even be Howard Lager. I think it kind of looks like him.

This next one is just Phil with another one of the farmhands. It might even be Howard Lager. I think it kind of looks like him.

Grammy Helen would have been 95 today. I am missing her something fierce because I wish I could share all these amazing discoveries with her.

Grammy Helen would have been 95 today. I am missing her something fierce because I wish I could share all these amazing discoveries with her. e picture that twisted my heart when I saw it. Phil and Joe in obviously-new suits, standing next to 8-year-old Anna Mae and 4-year-old Buddy, the Brenckles’ biological son.

e picture that twisted my heart when I saw it. Phil and Joe in obviously-new suits, standing next to 8-year-old Anna Mae and 4-year-old Buddy, the Brenckles’ biological son.

Recent Comments