That’s the title of my post because, well, it is.

I just got back from an all-day research binge in the library’s Pennsylvania Room.

I just got back from an all-day research binge in the library’s Pennsylvania Room.

I have a stack of census forms, a sheaf of photos and a whole lot of answers.

The biggest asset they have is access to ancestry.com, which I’ve been dying to join for ages.

The first thing I did was dig through their Census records. Thank goodness I’d found that will because I knew to search and verify information by everyone’s Italian name, rather than the Americanized version. Jackpot in the 1910 Census!

I now know that when my grandpa was 3, he lived with his mother, father, sister, brother and uncle Pasquale (who was listed as a boarder. Interesting.) on St. Andrews Street in East Liberty. I looked it up on Google Maps, but it doesn’t look like it exists anymore. But using Our Lady Help of Christians as a beacon, I was able to trace the boarders of his early life. The church is within walking distance of their house. Enterprise Street, where Saverina eventually moved, is only a few blocks over in the opposite direction.

This record has Francesco doing odd jobs, so I wonder if he’d been laid off. Maybe he was a Francesco was working for himself, kind of a freelance tailor?

I’d pictured them living in a walk-up apartment. Not real big. Maybe even something like this. But the address seems to indicate a house-house, rather than an apartment building where they might share a few rooms. All of their neighbors have different house numbers. Was it possible they lived in their own home, albeit a rented one? Francesco and Saverina had been married for 6 years. She’d had three children and three live births.

It made me smile to see the five of them and their uncle together. It’s the first real mental image I’d been able to conjure of my grandfather belonging to his birth family. And in this record, they really were.

Here’s a quick run-down of my other discoveries:

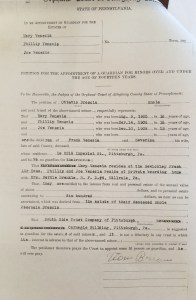

- Cesare and Pasquale Brescia, Saverina’s brothers, were part of a group of people known as “birds of passage.” They sailed back and forth between Italy without becoming citizens. I found records indicating that Cesare, the brother who’d come with his newlywed sister to America, would return to Italy in 1907 and 1913. He’d tried to come in 1912, but had come down with the dreaded eye disease trachoma and had been turned back. Pasquale, who’d also come in 1904, left in 1913 and returned in 1914. How and when Ottavio, the uncle from the Guardianship papers, came to the US remains a mystery

- Loads and loads of pictures from the ‘Italians’ picture collection. I now have a pretty good visual idea of what it was like to walk through the streets of East Liberty, how kids and adults dressed, what types of buildings and landmarks made up Phil’s life.

- Information about the Sewickley Fresh Air Home, where my great-aunt Mary lived much of her life. I’ll write a separate post about her later.

- Sanborn Fire Maps. Oh my god, I’m in love with them. Big digital maps that are overlaid. You can find all the old streets, see old buildings that were torn down, who owned them. And the best part about them is you can access them outside the library.

So, early this morning, I trundled into the Marriage License Bureau to start my digging there.

So, early this morning, I trundled into the Marriage License Bureau to start my digging there.

Recent Comments