My Mom handed me a small, brown wallet, clasp tantalizingly closed as if its owner had just placed it on the nightstand.

“I figured you’d want this,” she said, “It was Aunt Mary Vee’s.”

Mary “Vee,” my great-aunt, Mary Venezia, was the last link to Grandpa Phil, Great-Uncle Joe, and their parents. As the oldest child, she had the clearest memories of nearly all their shared tragedies. By the time she died at 73, she’d outlived her parents and siblings despite a congenital hip defect and tuberculosis that settled in her bones with spine-twisting brutality.

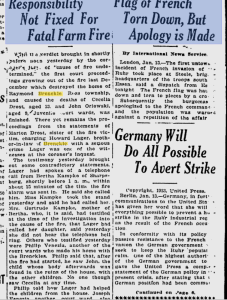

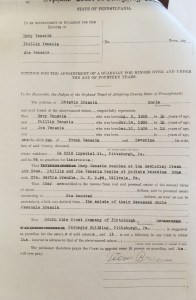

I say nearly because, in 1920, Mary’s destiny diverged from her brothers’. When they were pulled, sick and starving, from Pasquale’s hovel in Pittock, Phil and Joe went into Allegheny County’s rudimentary foster care system while Mary was sent to the Sewickley Fresh Air Home. A cross between Shriner’s Hospital and St. Jude’s, it provided care to children 14 and younger, mostly with polio, tuberculosis, and orthopedic complications. Someone — possibly Mary’s caseworker Camilla Barr — was looking out for her and negotiated 15-year-old Mary a place there, paid for by the county.

Despite having her family and heritage severed repeatedly, Mary saved pieces of her fragmented past with tender, orderly ferocity. She preserved the only photograph of Francesco and Severina, Francesco’s memento mori pin, and her baby picture.

With an archivist’s practiced eye, I unclipped the wallet’s slim band.

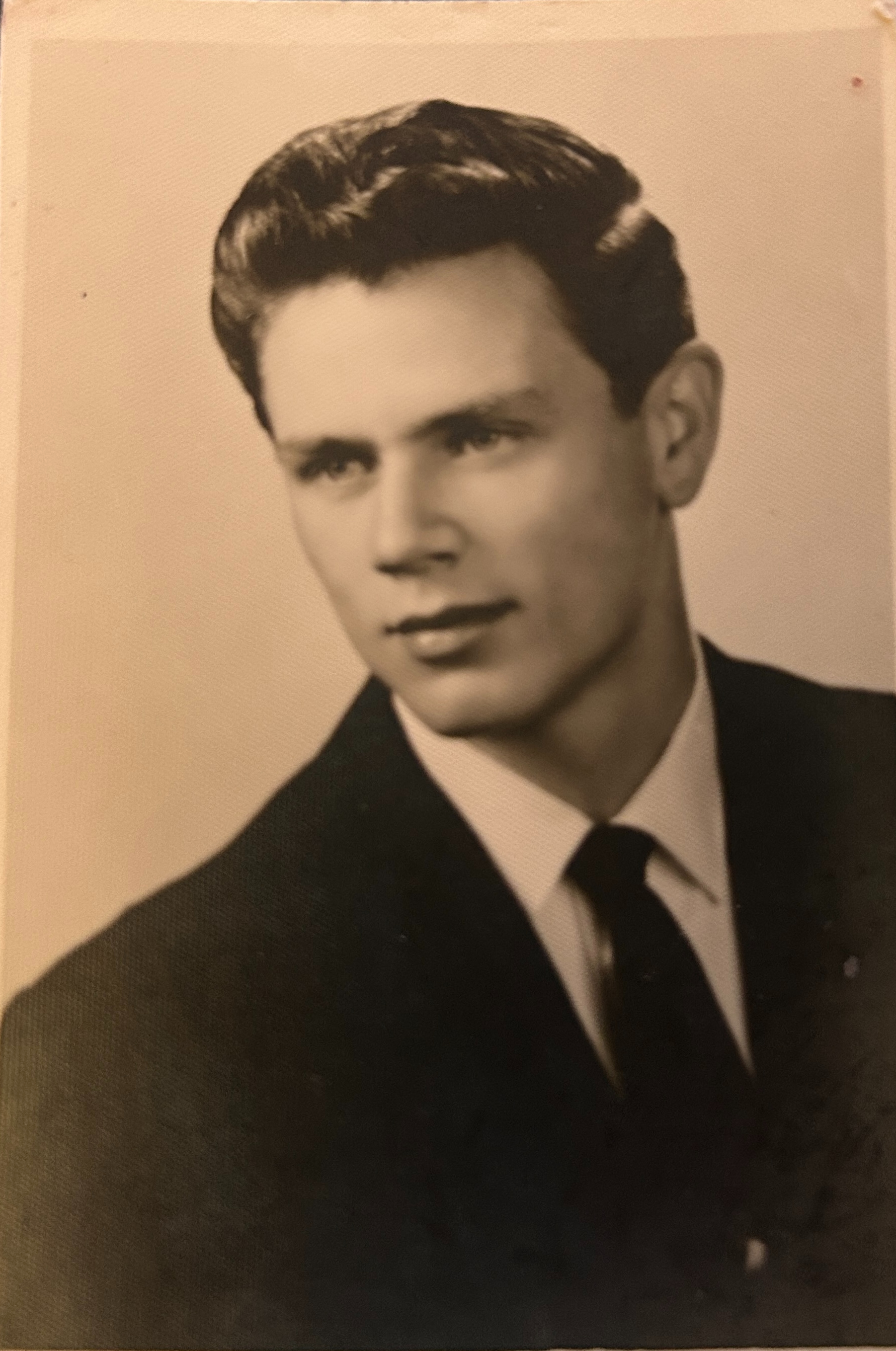

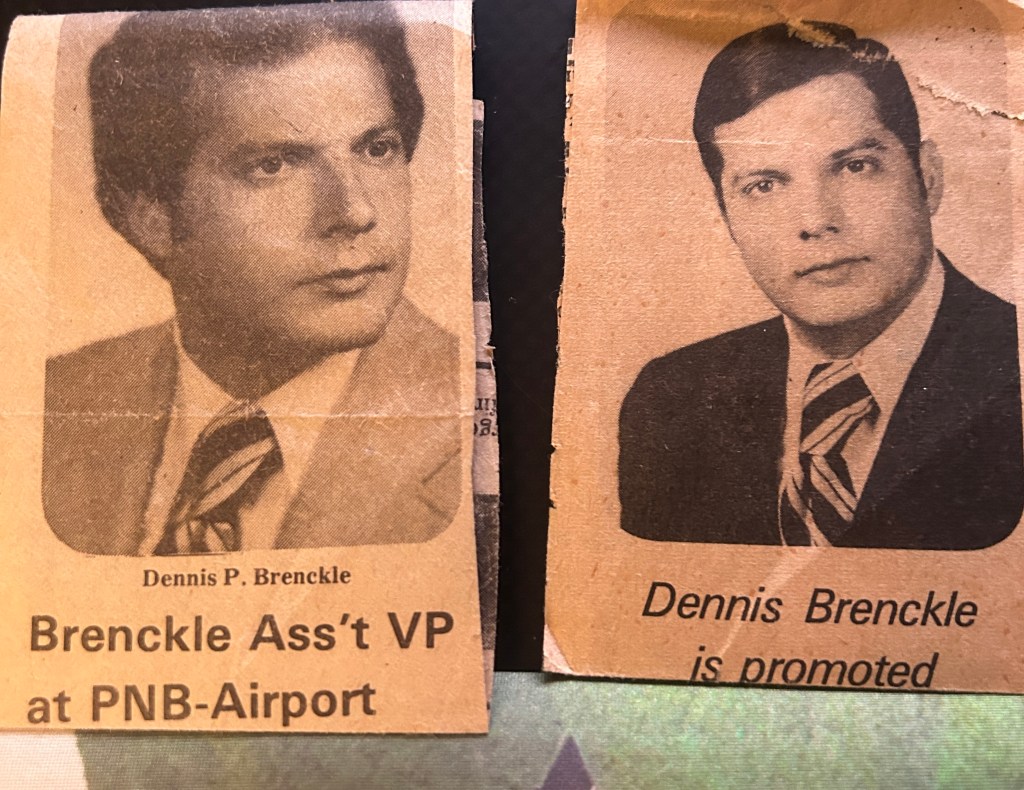

My Dad’s face, forty years younger, stared back from a pair of newspaper clippings announcing promotions at Pittsburgh National Bank, followed by two of Dad’s business cards with elegant, Palmer-script notations indicating he was her emergency contact.

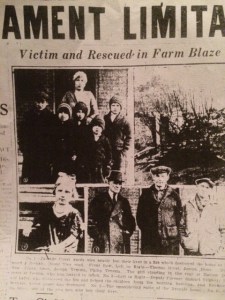

Next, to my surprise, was a photo of Joe and Phil. Taken the same day as another photo in my collection, I recognize the Brenckle farm lane in the background and conclude it was most likely after they’d returned from Bellaire. Their smiles are tighter, eyes shifting slightly left as if still on guard for danger. In faded pencil, Mary’d written on its back, “Phil and Joe in working clothes.”

Next came high school graduation photos of my Aunt Mary Ann and Joe’s children, Myrtle and Wayne; my cousin, Bryce, her first great-grand-nephew, at four months old.

Then, her social security (issued in 1970), health care (Blue Cross of Western PA), and voter registration (Republican) cards.

Finally, a small collection of strangers’ babies, graduation, and wedding photos. Every image, however, was marked with names, dates, and short descriptions. It was a reminder that Mary was not only a vital part of our family’s history but a sweet memory in so many others.

The 1951 Pittsburgh Press article about the Fresh Air Home noted that after healing, she’d remained there as a kindergarten teacher and was known to sit up nights holding the hands of new arrivals who missed their families.

Those little boys and girls remembered dear Miss Mary and wrote to her by the dozens over decades. At one point, we had a large bag filled with hundreds of black and white photos, clippings, and notes former Fresh Air residents sent. Babies, graduations, enlistments, and homecomings were all shared with the woman who’d been the friend they needed. I’d uncovered it in my parents’ closet at about age 10 and sifted through it endlessly. Several boys healed enough to be drafted into World War II. One sent photos from Eagle’s Nest, Berchesgarten, and several locations mentioned in Band of Brothers.

There were also photos of Mary and her Fresh Air friends having fun. After all, she was a young woman and emerged from three years of body casts with humor and an effervescent spirit. One letter preserved in the Bellaire stash included a note from Mary to Phil mentioning playing tricks on her doctor by stuffing newspaper in his shoes. Within the Fresh Air Home’s sprawling grounds, she strummed a ukelele, hosted little girls’ tea parties, and reenacted scenes from plays. Tragically, this cache fell victim to a basement flood and couldn’t be preserved, much like the Fresh Air Home itself.

Medicine and society moved from institutionalization to community care. The home shuttered in 1952, and Fresh Air’s wealthy benefactors gave Mary one final gift — a room at Friendship House, a genteel retirement home for upper-class ladies. However, her stay was contingent upon remaining mobile and self-reliant.

And for decades, she was. Until, one day, she wasn’t. The stately Sewickley Victorian, with her room on the top floor, was no place for a woman with severe spinal degeneration. A doctor convinced her surgery would save her mobility. Dad tried to talk her out of it, hearing chicanery’s quack a mile away. However, Mary, who’d fought valiantly for independence, decided to go down swinging. Complications predictably, fatally arrived.

Before she left this world, Mary learned my Mom was pregnant with me. She was overjoyed to know her favorite nephew, who looked so much like his father — the little brother she loved so much — would be a father himself. In a way, her precious, tiny collection of our family’s founding documents paved the way for all the research I conducted years later.

Mary, ever the teacher, also hid a final lesson in her tightly packed wallet. Its collection of family and friends reminds us that opportunities to treat others with kindness, mercy, respect, and love come to us all. Ripples of those choices reach untold generations, bearing memories that become blessings.

I just got back from the Brenckle Family Reunion. And oh boy, did I once again hit the motherlode.

I just got back from the Brenckle Family Reunion. And oh boy, did I once again hit the motherlode. This next one is just Phil with another one of the farmhands. It might even be Howard Lager. I think it kind of looks like him.

This next one is just Phil with another one of the farmhands. It might even be Howard Lager. I think it kind of looks like him.

I just got back from an all-day research binge in the library’s

I just got back from an all-day research binge in the library’s

Recent Comments