Over the weekend, I decided to take my new Ancestry membership out for a spin.

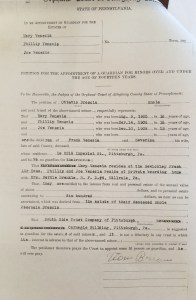

I’d gone back over the guardianship documents, including the two other pages I’d not really examined carefully until now and I realized I’d circled in on a new fact. I could place Phil with his family in 1910. Both of his parents were dead by 1917. By 1922, according to the trust documents, Phil and Joe been placed with the Brenckles and Mary was living at the Fresh Air Home. So, there were four missing years. Where did the three kids go?

Again, a fragment of a fragment set my direction. There were two things I remembered Grammy telling me about how Grandpa had come to live with the Brenckles.

“They lived with an uncle who was terrible to them. He was a drunk. He wanted them just for the money,” she’d said. I had always presumed that meant the money people get for taking in foster kids. But maybe it meant their father’s money.

When I’d asked if they’d ever lived in an orphanage, she said she remembered Toner Institute. I always thought it sounded ominous.

I started with the uncle. The next Census would have been in 1920, so I pulled up Ancestry and started searching there.I now had at least four different uncles to pick from. Who would it be?

“Patsy Ritonda?”

Patsy. Patsy. Duh. Patsy is short for Pasquale. How the Census-taker got Ritonda from Brescia I’ll never know. But I did note the taker’s name was German. I pictured two men with thick accents trying to understand each other — neither one caring much how questions were answered.

I found the siblings simply enough, though their names were again misspelled. If it’s one thing all this research has taught me, it’s that misspellings are just as important as correct ones — if the other material adds up. There’s a margin of error every time you look for someone. A birthday that’s a day or two off. A name spelled close, but not exact. I’ve learned that our vital information really wasn’t standardized until after World War II, when a lot of returning GIs leaned on their war records as official documents.

So, anyway, there they were, living on 41 Fleming Park Avenue in a place called Pittock, Stowe Township. When I found it on the map of Allegheny County, tucked between McKees Rocks and Kennedy Township, I realized that I had been there at least two dozen times. Grammy liked to go to the tiny Catholic Church in Pittock — instead of her usual St. Malachy’s — every once in a while.

I called my dad.

“Did your dad ever say anything about living in Pittock?”

“Yeah.” I could hear his voice catching the thread of memory. “He did. I remember one or two times, when we were driving into the Rocks, we’d go past the bridge and he’d say he used to live over there. I didn’t put it together until now. Why? You said he lived in East Liberty.”

“Because I think I found ‘the uncle.’ You know, the one who mistreated them? His name is here in the census as Patsy Ritonda.”

“Patsy Ritonda? Never heard of him.”

“It’s Pasquale, Dad. Your grandmother’s brother. The guy who left them the 1500 bucks. I think he’s the guy. They were living with him.”

We were both quiet. The thing is, more than “simple” hardship came out of the siblings’ time with their uncle. Grammy had told us it was during that time that Grandpa had contracted the strep throat that ended up weakening his heart. The heart that would eventually kill him long before his time, and just a year or so removed from the invention of life-saving valve replacement surgery that would have given him so many more years.

Joe, who was known his whole adult life by the extremely un-PC nickname of Crip (as in cripple, because he walked with a limp. oh boy), had fallen off a horse and broken his ankle. It had gone untreated. And Mary had contracted the tuberculosis that twisted her bones and stunted her growth.Three years in a body cast.

“That guy sucks,” I finally said.

As we hung up, something at the top of the third paper caught my eye. I shuffled back and forth between the computer screen and the paper.

The guardianship papers had Pasquale’s date of death as November 29, 1920 at Woodville State Hospital. A quick cross-reference (thanks again, Google!) revealed that Woodville was a home for the insane (gulp). But they also took a fair amount of tuberculosis patients. That was more likely, and it explained Mary’s exposure. If she had somehow managed to fight it off when her father was sick, being exposed by Pasquale was surely too much.

The census had been taken in January of that year. By the time that census taker reached their door, the siblings were living on borrowed time. I searched for Pasquale again, using a variety of misspellings, and pulled up a World War I draft card, filled out June 5, 1917 — five months after Saverina died.

It was requesting an exemption to the draft because he was “sole support of three nieces (sic).”

The address was the same. The job was the same. And so was the place of birth.

I had my man.

But beyond that, I had a real timeline now, and an apparent chain of custody. From both parents to their mother to Pasquale to the county.

But my mind flipped back to good old Mike Natale. He was their stepfather, for pete’s sake. Why didn’t he keep them and their half-sibling together?

I’ve filled out my request for the Coroner’s Inquest. It’s times like this I’m so happy I work in news. I feel like what I do for a living prepared me for tackling this big mystery.

I’ve filled out my request for the Coroner’s Inquest. It’s times like this I’m so happy I work in news. I feel like what I do for a living prepared me for tackling this big mystery. I just got back from an all-day research binge in the library’s

I just got back from an all-day research binge in the library’s

Recent Comments