It still doesn’t feel real. Twenty years after I put my head down on a lonely desk in an empty newspaper office and pulled it up with his image burning across my brain, this journey Grandpa Phil and I took together meets its incredible conclusion. I have a book deal.

On May 13, I signed with Sunbury Press to publish Three Rivers Home.

While there’s still so much to do (developmental editing, more beta reads, fact-checking), I’m reveling in the joy this moment brings.

It will be real, on a shelf, just like the thousands of books that shaped my childhood and adulthood. What’s more, in seeing a little boy who lost everything thrice over survive, readers might find strength to get through their hardest days.

Last week, I got to share I the happy news with my amazingly supportive friends at Pennwriters during our annual conference. It was at the 2024 event in Lancaster that I met Lawrence Knorr, Sunbury’s CEO, and pitched my manuscript. Returning to Pittsburgh, where I’d begun pitching, was an especially sweet, full-circle moment. The talented colleagues I’ve met through Pennwriters are an invaluable source of inspiration, information and generosity. One theme running through Three Rivers Home is finding where you belong. Like stepping through the doors of Ursuline Academy, onto the portico at the E.W. Scripps School of Journalism or into newsrooms across Pennsylvania, there’s something soul-settling about gathering with my fellow writers.

So, what have I learned across two decades, thousands of hours, multiple rejections and more than one computer disaster that almost ate all my hard work? The same thing Grandpa Phil did: Just.Keep.Going.

Satisfying endings aren’t guaranteed. It’s only in looking back that all the connections seem to point toward success. In reality, nothing’s certain — except that giving up ensures failure.

The family Grandpa and Grammy created remains. Not all in Pittsburgh, but we are together, living in a future I’m not sure either could imagine. The family his story created — through writing groups, compassionate beta readers, encouraging friends and helpful historians — will add new members as the book launches (date to be determined.)

Music has been another constant through this journey. From Phil’s mysterious, one-time performance of “Sweethearts on Parade” to the “Hamilton” and “Moana” soundtracks that soothed the pandemic’s depths and inspired me to keep trying. It wasn’t a surprise when a song I’d long forgotten found me again. “Almost Home,” off Mary Chapin Carpenter’s “Party Doll and Other Favorites” album, rang out as the Squirrel Hill Tunnel’s darkness gave way to a bright May morning shining over the city view that never fails to take my breath away. It’s an amazing feeling, isn’t it? Knowing whatever journey you’ve completed is past, and you’re returning to a place of safety and rest. I imagine, had it existed in 1924, the words would have resonated with Phil and Joey, too. As the horrors of their childhood receded, the boys walked out of Allegheny County Courthouse as part of a family and headed back to Troy Hill. They weren’t running. They weren’t hiding. They were almost home.

Grammy Helen would have been 95 today. I am missing her something fierce because I wish I could share all these amazing discoveries with her.

Grammy Helen would have been 95 today. I am missing her something fierce because I wish I could share all these amazing discoveries with her.

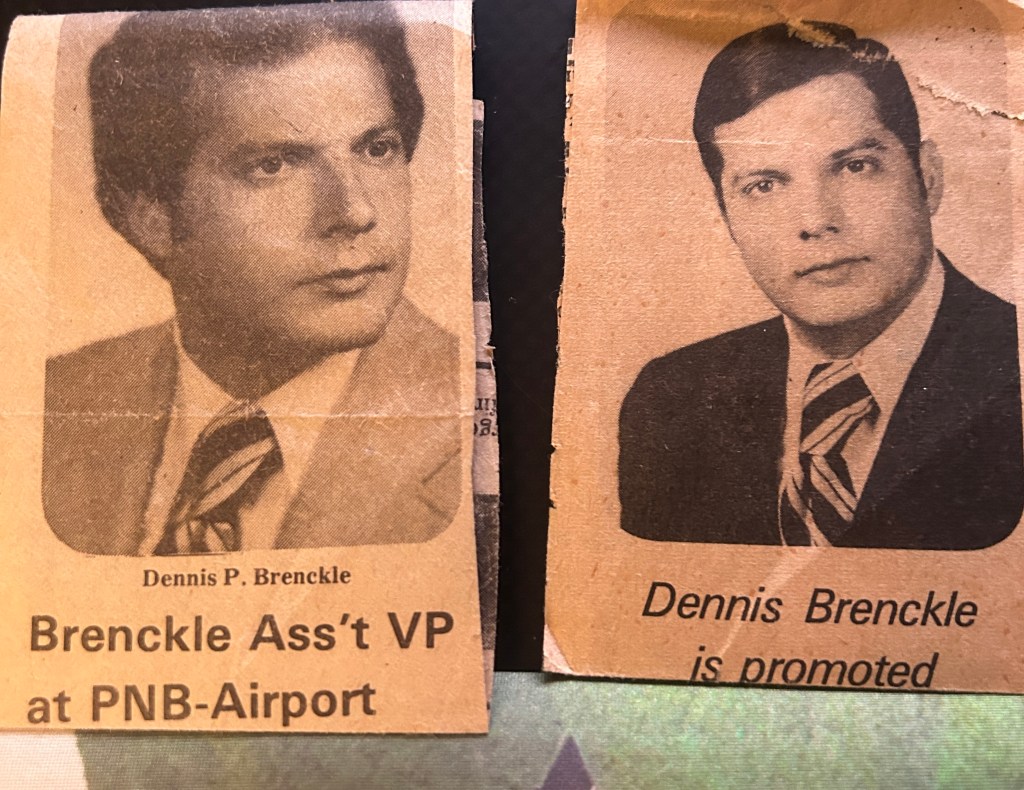

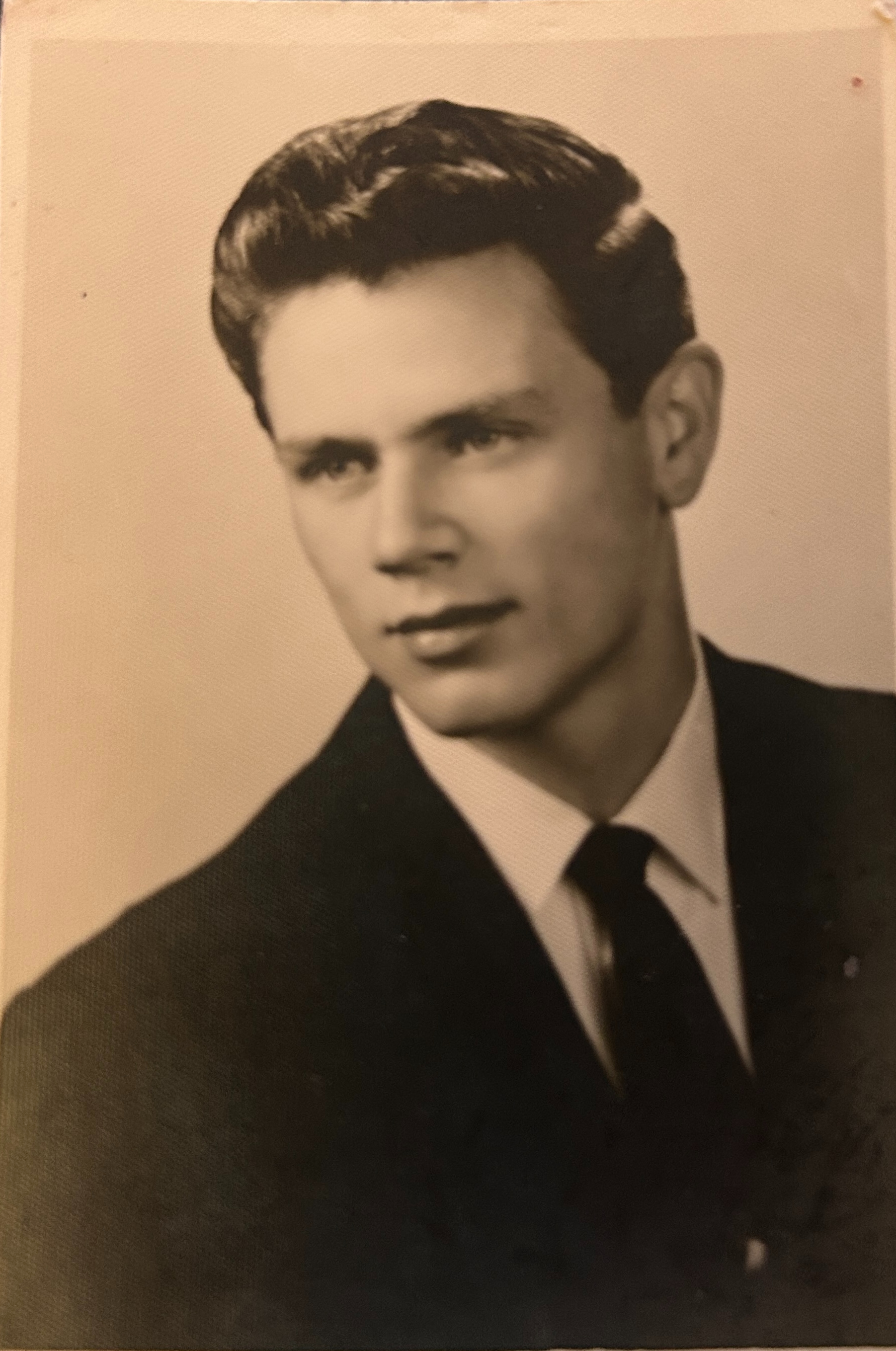

e picture that twisted my heart when I saw it. Phil and Joe in obviously-new suits, standing next to 8-year-old Anna Mae and 4-year-old Buddy, the Brenckles’ biological son.

e picture that twisted my heart when I saw it. Phil and Joe in obviously-new suits, standing next to 8-year-old Anna Mae and 4-year-old Buddy, the Brenckles’ biological son.

Recent Comments